Preface

Polymer Morphology means the way polymer chains are arranged in the solid state. The simplest three variable characterisation is:

- Degree of crystallinity among the chains

- Proportion of orientation among the chains not in crystals

- Direction of the orientation

Wood is a natural material with highly oriented chains, which give it its well-known directional properties. Thermoplastic polyester is a familiar textile fibre in which both the non-crystalline and crystalline fractions are deliberately oriented along the thread-line to confer strength which can, if required, exceed that of drawn steel.

Glass fibres play the same role in polymers whose chains are not so easily oriented in preferred directions. In glass reinforced plastics (GRP) the desired orientation is often achieved by weaving glass mats[1], placing them in a mould and spreading a short chain polymer[2] over and into them. The polymer chains are then caused to link up by the action of thermally activated catalyst dissolved among them[3]. In this form the material is no longer “plastic” despite its common name of GRP.

When carbon fibres are used instead of glass, and “epoxy” resins are used instead of polyester[4] resins, you get the standard forms of carbon fibre composites used in racing cars, aircraft, golf clubs and tennis rackets[5].

When glass (or carbon) fibres are used with mainly saturated polymer chains, polypropylene and nylon for instance, they are usually in short lengths by comparison with the principal dimensions of the artefact which is to be fabricated, so that they are not seen on the artefact’s surface and succeed in penetrating into its crevices.

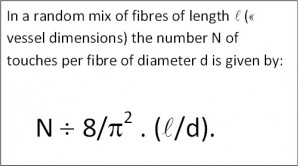

One of the two biggest challenges in manufacturing mouldings and extrusions has been to ensure that the discrete fibres are oriented in the directions of greatest stress when the artefact is put into use. In pipe extrusions, discrete fibres will orient naturally in the direction of extrusion, i.e. along the pipe axis, whereas the greatest stress in a pipe under internal pressure is circumferential, i.e. at right angles to the extrusion direction. Overcoming this problem has been the focus of the SAFIRE© technology. Many of the papers listed in the panel are concerned with the fundamental science of the SAFIRE technology, a key result of which is the touch equation.

The second of the two biggest challenges is to ensure that the glass or carbon fibres actually contact the host polymers at the molecular level. Ways of ensuring this are also part of the SAFIRE technology, but as discussed in the papers opposite, they are dependent on the chemistry of wetting, developed in the 1980s by BP Chemicals among others.

References

[1] As found in home and car repair kits.

[2] Usually referred to as resin.

[3] Microwaves have proved an effective replacement for normal heating.

[4] These so called “unsaturated” polyesters are quite distinct from the thermoplastic polyesters used to make textile fibres.

[5] Carbon fibre is not as strong as glass fibre for a given cross-section, but it is stiffer than glass, a desirable property in the above applications.